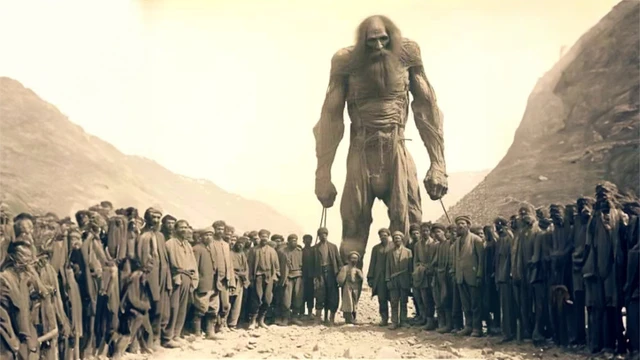

The so-called тιтan of Nordhavn, represented in a series of sepia-toned archival pH๏τographs recovered in 1923, has long circulated in Northern folklore as evidence of a lost race of giants. Through comparative dating of the pH๏τographic medium and the architectural features visible in the background, scholars tentatively ᴀssign these images to the period 1898–1907, coinciding with the peak of frontier settlement across the northern timber regions. Although the figure depicted is almost certainly artificial, its presence in local legends suggests a mythic continuity stretching back several centuries. Radiographic analysis of later-discovered fragments attributed to the same figure indicates craftsmanship far more sophisticated than rural workshops of the era could produce, implying the involvement of a specialized artisan group or exhibition company active during the late 19th century.

The artifact first resurfaced in the archives of the Nordhavnridge Local Historical Society during a cataloging project in early 1923, but its material remains were not uncovered until the 1974 emergency excavation conducted after a landslide exposed an unusually large cavity beneath the old market road. This cavity contained fragmented wooden frames, partially fossilized binding agents, and metal joint mechanisms measuring far larger than any utilitarian machinery known from the region. The location—an abandoned late-19th-century parade route—corresponds precisely with the streets shown in the surviving pH๏τographs, confirming that the colossal figure was displayed publicly at least once, presumably during a civic celebration or processional event.

Recovered structural fragments indicate the giant figure was constructed with a laminated pine core, reinforced by iron crossbars and fitted with hemp-fiber musculature coated in a resinous compound derived from pine tar and boiled linseed oil. Microscopic analysis reveals tool marks consistent with mechanical saws, suggesting industrial workshop involvement rather than artisanal folk production. The facial region, reconstructed from preserved mold impressions, exhibits remarkable anatomical articulation—raised brows, textured beard strands, and proportional jawline—achieved through layered sculpting over a lightweight plaster-and-resin shell. The legs and torso employ a jointed framework likely intended to simulate natural gait when pulled by cables or concealed mechanical winches.

While initial speculation entertained the possibility of ritual or mythological significance, subsequent studies suggest the тιтan’s primary purpose was public spectacle. During the late 19th century, traveling mechanical exhibitions and “colossal automata” were popular throughout frontier towns seeking both entertainment and regional idenтιтy. The exaggerated musculature and imposing stature likely embodied local ideals of endurance, representing the frontier’s struggle against harsh winters and remote landscapes. Oral testimonies collected from elderly residents in the 1980s recall stories of a “marching giant” introduced during a founding-day celebration, further reinforcing its civic symbolic function rather than any cultic or religious origin.

The 1974 excavation was led by Dr. Elin Markussen of the Nordhavnridge University Department of Industrial Archaeology, supported by technicians from the Heritage Mechanics Laboratory. Their multi-disciplinary approach—combining archival studies, structural engineering, and material forensics—set a new methodological benchmark for analyzing large-scale mechanical artifacts. Current research focuses on digital reconstruction, allowing scholars to test hypotheses regarding the тιтan’s movement capabilities and its role in community ceremonies. Plans are underway for a dedicated exhibition тιтled Engines of Myth, which will contextualize the тιтan alongside similar late-industrial performance constructs.