The funerary mask of Pharaoh Tutankhamun is one of the most iconic artifacts of ancient Egypt, discovered in 1922 within Tomb KV62 in the Valley of the Kings, near Luxor. The tomb was unearthed by British archaeologist Howard Carter under the patronage of Lord Carnarvon. Tutankhamun ruled during the late 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom, approximately 1332–1323 BCE. Unlike most royal tombs of the period, KV62 was found largely intact, offering an unparalleled archaeological context for understanding royal burial practices.

The funerary mask is crafted primarily from solid gold, weighing approximately 11 kilograms, inlaid with semi-precious stones including lapis lazuli, quartz, obsidian, turquoise, and carnelian. The gold sheets were hammered and polished with extraordinary precision, while the inlays were meticulously set to define the eyes, eyebrows, and royal insignia. The mask combines idealized facial symmetry with symbolic elements such as the nemes headdress, cobra (uraeus), and vulture, representing divine kingship and protection. This level of craftsmanship reflects both advanced metallurgical knowledge and religious symbolism.

In ancient Egyptian belief, the funerary mask served as a spiritual interface between the physical body and the soul (ka and ba). It was designed to preserve the idenтιтy of the deceased and enable recognition in the afterlife. The idealized features were not intended to be a literal portrait but a divine transformation, aligning the king with Osiris, god of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ. The mask thus functioned as both protective armor and a metaphysical vessel ensuring resurrection and eternal rule beyond death.

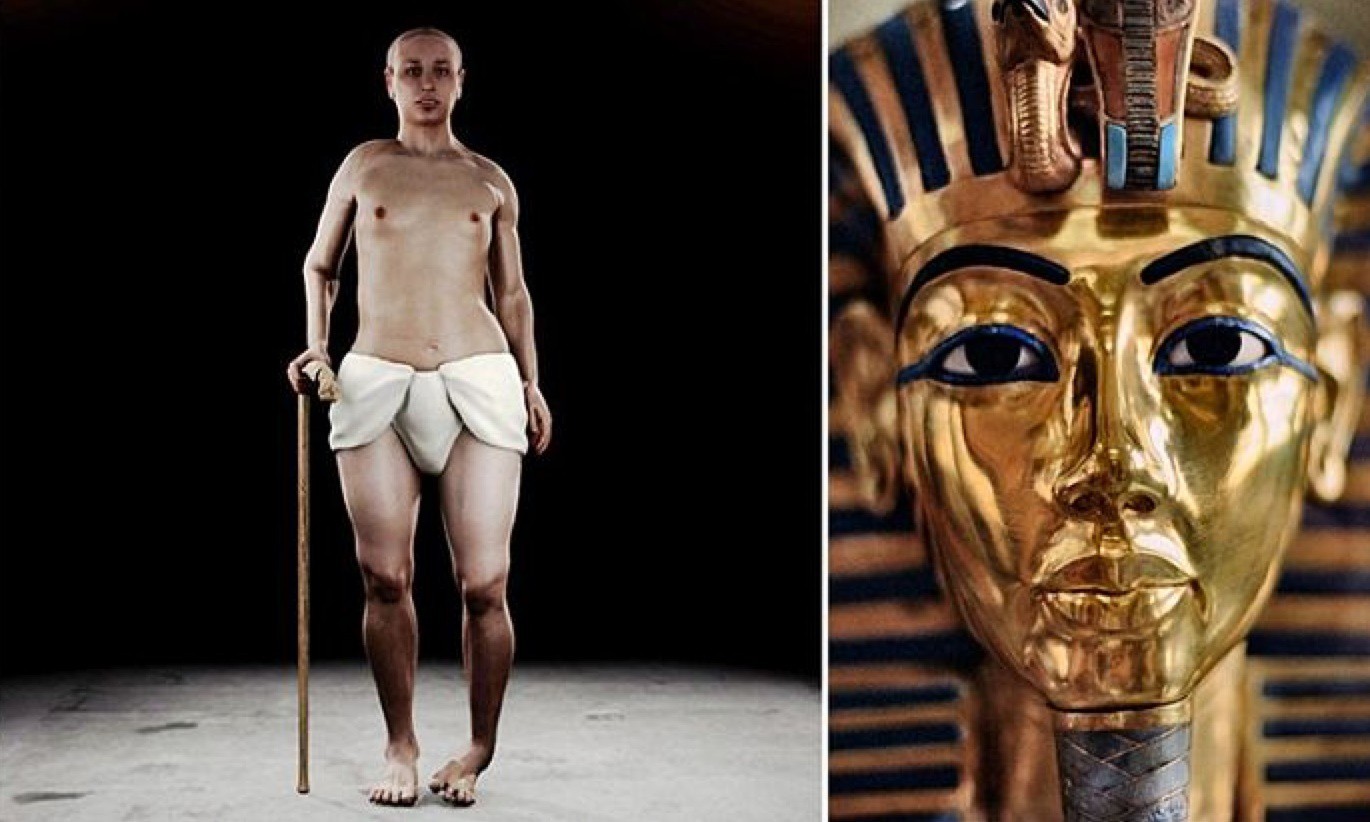

Modern scientific studies, including CT scans and forensic facial reconstruction conducted by international teams in the early 21st century, have provided insight into Tutankhamun’s actual physical appearance. These reconstructions reveal a young man with delicate facial features, physical ailments, and a less idealized form than the golden mask suggests. The contrast between the human face and the divine mask highlights the deliberate transformation imposed by royal funerary art. Insтιтutions involved include Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities and multidisciplinary research teams from Europe and North America.

The juxtaposition of the golden mask and the reconstructed human form provides profound insight into ancient Egyptian concepts of idenтιтy, power, and eternity. It underscores archaeology’s role in distinguishing symbolic representation from biological reality. Tutankhamun’s mask is not merely an object of beauty but a carefully constructed statement of kingship, theology, and cultural values. Continued study of such artifacts deepens our understanding of how ancient societies negotiated mortality, memory, and divine legitimacy.