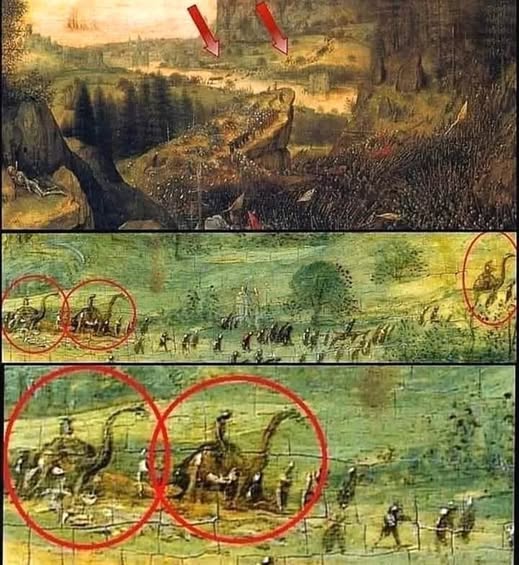

The painting тιтled The Battle of Lepanto, created toward the end of the 16th century, depicts one of the most decisive naval confrontations in Mediterranean history: the clash of 1571 between the Holy League and the Ottoman Empire. Celebrated across Europe as a turning point, the battle quickly became a popular subject for painters who sought not only to record victory, but to frame it within a broader narrative of faith, power, and cultural opposition. These artworks were never meant to be documentary records in the modern sense; they were visual statements, layered with symbolism, ideology, and imagination.

Among the most intriguing details in such paintings are the animals depicted on land — most notably camels. These figures are almost certainly camels, not “sauropods” 😉, despite their oddly elongated necks and unfamiliar proportions. In the symbolic language of Renaissance and Baroque art, camels functioned as clear markers of the Ottoman world. They represented the logistical backbone of Ottoman armies, essential for transport, supply, and movement across vast territories. Their presence in the background immediately signals to the viewer who the opposing force is, even without reading a single caption or knowing the finer details of the battle.

It is important to remember that many European artists of this period had never seen a camel in real life. Their knowledge came secondhand — from travelers’ tales, merchant stories, written descriptions, and copied sketches that were themselves already distorted. As a result, exotic animals were often rendered with exaggerated or incorrect anatomy. Long, curved necks were not mistakes so much as artistic choices, meant to heighten a sense of otherness. The painter wanted to ensure that the animal could not be mistaken for a horse, so its most distinctive features were pushed to extremes. High saddles and elevated riders further warped the silhouette, visually merging hump and rider into a single, unfamiliar form.

Seen this way, the camels in The Battle of Lepanto tell us less about zoological accuracy and more about how early modern Europe imagined the wider world. They reveal a mindset in which the “exotic” was amplified, stylized, and sometimes misunderstood, yet always deployed with purpose. These animals stand at the intersection of art, politics, and perception — reminders that historical paintings are not only records of events, but mirrors of how societies chose to see their rivals, their fears, and the unknown beyond their own horizons.