The Gate of the Sun, located at the archaeological site of Tiwanaku near Lake тιтicaca in present-day Bolivia, is one of the most iconic stone monuments of pre-Columbian South America. Archaeological consensus places its construction within the Tiwanaku civilization, roughly dated between 500 and 1000 CE, although some scholars argue for an earlier phase based on stylistic and astronomical interpretations. Carved from a single mᴀssive block of andesite stone weighing approximately ten tons, the monument demonstrates an extraordinary level of planning, quarrying, transport, and stone-working skill. Andesite, a volcanic rock of exceptional hardness, was deliberately chosen, suggesting not only technological competence but also symbolic value attached to permanence and sacred power.

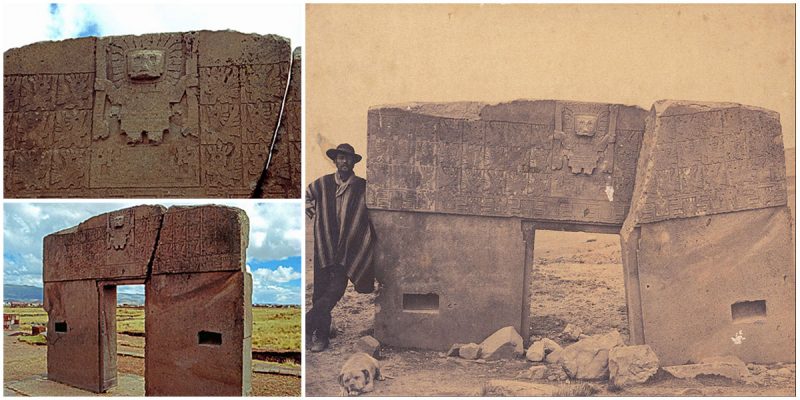

The upper lintel of the Gate of the Sun is decorated with a complex relief depicting a central anthropomorphic figure, commonly identified as a Staff God or solar deity, surrounded by rows of winged attendants or mythological beings. The iconography is highly standardized, geometric, and deeply symbolic, reflecting a cosmological system rather than narrative art. Many researchers interpret the relief as a calendrical or astronomical representation, possibly linked to solar cycles, agricultural seasons, and ritual timekeeping. This reinforces the interpretation of the monument as a ceremonial or ritual gateway rather than a functional architectural entrance.

Historical pH๏τographs from the early twentieth century, particularly those taken around 1903, show the Gate of the Sun in a collapsed and fractured state, lying horizontally with visible cracks and displacement. This condition is generally attributed to long-term environmental stress, seismic activity, and possible post-collapse human interference rather than deliberate destruction. During the twentieth century, the monument was re-erected and restored to an upright position, resulting in the current appearance seen in 2024. While this restoration allowed for preservation and public display, it has also raised ongoing debates among archaeologists regarding authenticity, reconstruction accuracy, and the loss of original contextual information.

From an archaeological perspective, the Gate of the Sun is not merely a monumental sculpture but a material expression of Tiwanaku political authority, religious ideology, and technological capability. Its survival—despite collapse, restoration, and centuries of exposure—continues to provide critical data for understanding Andean civilization before the Inca. Rather than evidence of lost super-civilizations or anachronistic technologies, the monument stands as testimony to the sophistication of indigenous societies whose achievements were long underestimated. The contrast between its condition in 1903 and 2024 reflects not mystery, but the evolving relationship between archaeology, conservation, and modern interpretation.