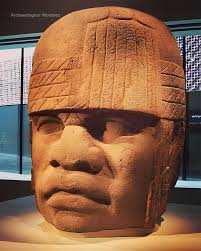

From the perspective of an archaeologist with twenty years of fieldwork behind me, this sculpture speaks with an unmistakable authority. This is a colossal Olmec head, carved from solid basalt, dating roughly between 1200 and 400 BCE—one of the earliest monumental art forms in Mesoamerican history. Such heads were not merely sculptures; they were statements of power, idenтιтy, and memory carved into living stone.

The facial features are strikingly individualized: broad nose, full lips, and a stern, almost contemplative expression. This is not an idealized god, but a real human presence—most scholars agree these heads represent Olmec rulers, immortalized to ᴀssert political legitimacy and ancestral lineage. The helmet-like headdress, incised with subtle bands and grooves, likely reflects protective gear worn in ritual ball games or symbols of rank tied to leadership and warfare.

What years of excavation teach you is how much effort lies behind such silence. The basalt used here was quarried dozens of kilometers away, transported without wheels, metal tools, or draft animals—an extraordinary feat of organization and labor. Tool marks still visible on the surface reveal repeated stone-on-stone carving, a slow dialogue between human intent and geological resistance.

Weathering patterns along the cheeks and brow suggest centuries of exposure before burial or relocation, reinforcing the idea that these heads once stood in open ceremonial centers, watching over plazas filled with ritual, trade, and political drama. Encountering such a face in person is unsettling in the best way—it does not feel ancient in spirit, only distant in time.

This sculpture is not just an artifact. It is a portrait of authority, endurance, and cultural confidence—an unblinking reminder that complex civilizations thrived in the Americas long before written history recorded their names.