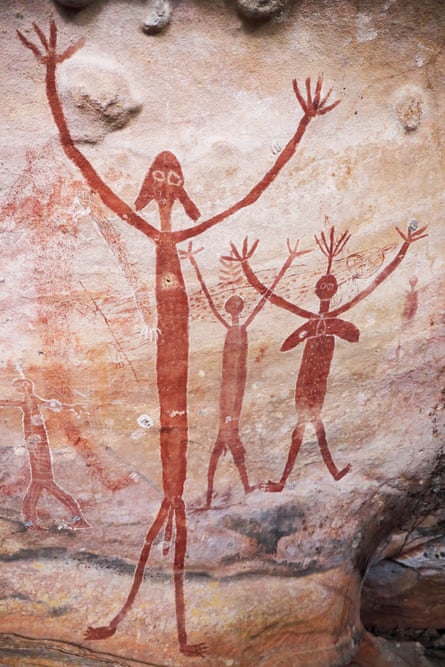

The extraordinary rock painting depicted above belongs to the Wandjina and Gwion Gwion artistic traditions of the Kimberley region in northwestern Australia, dated broadly between 15,000 and 4,000 years ago, depending on stylistic and pigment analyses. This specific motif—featuring a radiant humanoid with concentric circles for a face—was discovered during a documented survey of sandstone shelters by an interdisciplinary Australian archaeological team in the late 20th century, working in collaboration with local Aboriginal custodians. The site lies deep within a rugged sandstone mᴀssif, accessible only by foot through steep escarpments, signifying that it was deliberately chosen as a sacred or ritually significant location.

The painting was executed using iron oxide-based ochre pigments, a material widely exploited by ancient Aboriginal communities for its durability, vivid hue, and spiritual ᴀssociation with the land. Artists likely mixed powdered ochre with plant resins, animal fat, or water to produce a stable paint. Application methods included finger painting, fine brushes made from fibrous twigs or animal hair, and possibly blow-painting through hollowed bones. The rock ceiling, composed of weathered sandstone with a naturally rough but adherent surface, provided an excellent canvas that helped preserve the pigment for millennia. The radiating lines around the figure’s head show controlled, deliberate strokes, indicating a highly skilled artisan familiar with symbolic conventions.

The central figure—with elongated limbs, radiant head, and an upright, commanding posture—embodies a supernatural or ancestral being. Rock art researchers interpret the concentric circle face as a symbol ᴀssociated with cosmic power, spiritual vision, or weather-controlling enтιтies venerated by Kimberley peoples. Surrounding smaller figures appear to be dancers, attendants, or community members participating in a ritual scene. Their dynamic postures imply movement, possibly representing initiation ceremonies or mythological reenactments. The entire composition suggests that the site functioned not merely as a shelter but as a ritual stage, where stories about creation, morality, and cosmology were transmitted orally and visually.

From an archaeological perspective, such rock paintings served multiple functions: spiritual communication, territorial marking, and the preservation of collective memory. For the Aboriginal groups of the Kimberley, art was not merely decorative but an active medium connecting the living with the Dreamtime—the spiritual epoch believed to precede and shape the physical world. The radiant figure may represent a weather deity, a creator ancestor, or a guardian spirit invoked for protection, rainfall, or successful hunting expeditions. Its placement in a high, sheltered rock cavity would amplify its ceremonial significance, transforming the cave into a pilgrimage site where generations returned to reaffirm idenтιтy and sacred law.

The modern documentation of this site is credited to a joint expedition involving archaeologists, anthropologists, and representatives of the local Aboriginal ranger groups—most prominently members of the Wunambal Gaambera and Ngarinyin communities, who are recognized as traditional custodians. Their oral histories guided researchers in identifying sacred zones and interpreting motifs. Academic insтιтutions such as the University of Western Australia and various heritage organizations contributed to pigment sampling, radiocarbon testing of ᴀssociated organic remains, and digital preservation. Importantly, the research followed an ethically grounded, community-led approach: no physical removal of the artwork occurred, and all interpretive frameworks were reviewed by Indigenous elders to ensure cultural accuracy and respect.