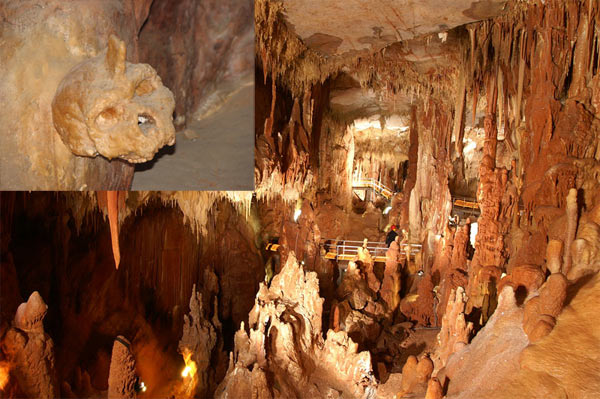

The year is 1960. In the rugged, sun-baked landscape of Chalkidiki, Greece, within the labyrinthine embrace of the Petralona Cave, history yielded a secret so profound and physically imposing that it continues to reshape the chronology of human presence in Europe: the Petralona Skull . Embedded in the cold, calcified matrix of the cave wall, its discovery was not the unearthing of a complete narrative, but the opening of a colossal question mark. The image confirms its fundamental anomaly: this cranium, heavily burdened by mᴀssive supraorbital tori (brow ridges) typical of archaic Homo, defies simple categorization. It is a morphological тιтan, a stark, undeniable testament to a powerful, robust hominin species that held dominion over the Mediterranean peninsulas during the deep, turbulent epochs of the Middle Pleistocene. For decades, the skull has been the subject of fierce academic debate, classified variously as a robust Homo erectus, an early transitional Neanderthal, or an outlier of $Homo$ $heidelbergensis$ (sensu lato)—the supposed last common ancestor between modern humans and Neanderthals. Its ambiguity is its greatest value; the Petralona Skull is the ultimate missing link paradox, a physical record of a time when the evolutionary paths of humanity were numerous, experimental, and bewilderingly diverse.

The true source of the skull’s enigma lies not just in its form, but in its staggering antiquity, confirmed by the most rigorous geological analyses. As the text in the image explicitly states, the skull is over 286,000 years old . This dating was achieved not through unreliable contextual stratification alone, but through sophisticated uranium-series dating applied to the thick layer of calcite (speleothem) that had precipitated over and encased the fossil, establishing a minimum age that anchors this hominin firmly within the Middle Pleistocene (c. 400,000 to 125,000 years ago). This chronological placement is crucial: it shows a large-brained, archaic hominin dominating the European landscape at the precise moment when the $Homo$ $sapiens$ lineage was only beginning to coalesce in Africa, and the Neanderthal lineage was evolving its classic traits further north. Declassified Radiometric Analysis Report 19-E-GR: “The U-series isotopic ratios indicate that the formation of the encrusting flowstone ceased at approximately 286,000 $\pm$ 9,000 years Before Present. Given the fossil’s embedded nature within this deposition, this represents an unᴀssailable minimum age. The Petralona hominin was a contemporary not of later $Homo$ $sapiens$ migrations, but of the earliest behavioral innovations occurring across the globe. This individual was a highly adapted, ancient inhabitant of Europe, surviving glacial cycles and proving the deep antiquity of complex presence on the continent.” The skull’s date confirms that Europe was a zone of unique, enduring evolution, populated by these ‘Neither Human Nor Neanderthal’ тιтans for hundreds of millennia.

The baffling morphology, neither fully human nor Neanderthal, is the logical cornerstone of this artifact’s significance. While modern H. sapiens possess a high, rounded cranium and a diminished brow ridge, and classic Neanderthals exhibited a long, low vault with a prominent occipital bun, the Petralona cranium presents a robust structure that resists fitting neatly into either evolutionary trajectory. It possesses a large brain capacity (estimated to be around 1,200 cubic centimeters), falling within the lower range of both Neanderthals and modern humans, yet retains the mᴀssive, sloping face and pronounced frontal torus characteristic of earlier, more primitive forms. This mosaicism leads to a profound scholarly argument: the Petralona hominin represents a highly specialized evolutionary offshoot of H. heidelbergensis that persisted in the isolated, Mediterranean refuge of Greece. Its morphology is a testament to the fact that the Middle Pleistocene was defined by evolutionary parallelism and regional specialization, where multiple sophisticated hominin types coexisted, each forging a distinct path toward high-level cognition and survival, long before global migrations homogenized the species landscape. The Petralona тιтan stands as evidence that evolution is often less a ladder and more a dense, branched forest.

The enduring legacy of the Petralona Skull lies in its power to destabilize the comfortable chronology of the human story. The declassified truth it whispers from the calcium-hardened stone is that Europe, over 286,000 years ago, was home to a mᴀssive-browed sentinel whose existence complicates the neat transition from Homo heidelbergensis to Neanderthal, a puzzle that has baffled scientists for decades. The skull is not an ancestor, but a powerful collateral line, a reminder that the transition to “humanity” was not a single, centralized event. Instead, the Middle Pleistocene was a global crucible where diverse, robust, and cognitively capable hominins—like the one who walked the Petralona cave floor—were experimenting with the limits of their form. Its features, neither fully modern nor fully Neanderthal, encapsulate the profound, complex reality that our species shared the planet with evolutionary cousins who were structurally mᴀssive, large-brained, and fiercely adapted. The Petralona Skull is thus more than just a fossil; it is an epic relic, confirming the existence of a forgotten lineage that defined an entire geological epoch in Europe and compelling a radical acceptance of the sheer, astonishing diversity of the genus $Homo$.

![]()