The Great Sphinx of Giza is one of the most iconic and enigmatic monuments of ancient Egypt, located on the Giza Plateau on the west bank of the Nile, near present-day Cairo. The statue is generally dated to the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, around 2558–2532 BCE, during the reign of Pharaoh Khafre. Archaeological consensus places its construction within the broader architectural complex of Khafre, including the pyramid, valley temple, and causeway. However, the Sphinx has long been the subject of debate due to unusual erosion patterns, undocumented cavities, and later modifications visible in both ancient and modern excavations.

The Sphinx was carved directly from the natural limestone bedrock of the plateau, rather than ᴀssembled from separate stone blocks. This limestone varies in hardness, resulting in differential weathering that is clearly visible today. The core body consists of softer geological layers, while harder limestone was used in certain reinforced areas, such as parts of the head. Tool marks indicate the use of copper chisels, dolerite pounding stones, and abrasion techniques typical of Old Kingdom stone-working. Later restorations, particularly during the New Kingdom and Roman periods, involved the addition of limestone blocks and plaster to stabilize eroded sections.

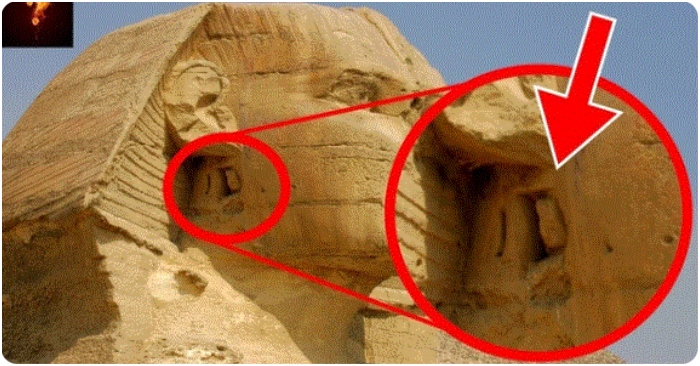

Multiple shafts, cavities, and openings have been documented around and on the body of the Sphinx, including behind the head, along the spine, and near the base. Some of these features were identified during modern archaeological surveys conducted in the 20th century, while others appear in historical pH๏τographs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys conducted by Egyptian and international teams revealed anomalies beneath the statue, suggesting the presence of voids or chambers. While some openings are clearly ᴀssociated with restoration work or drainage systems, others remain unexplained and continue to provoke scholarly debate.

From an archaeological standpoint, the Sphinx is widely interpreted as a guardian figure, symbolizing royal power and divine protection. The lion’s body represents strength and authority, while the human head—believed to bear the likeness of Khafre—embodies kingship and divine order (Ma’at). Subterranean features may have served practical purposes such as structural stabilization, ritual access, or drainage. Alternatively, some scholars propose symbolic or ceremonial functions linked to solar worship, given the Sphinx’s eastward orientation toward the rising sun. However, no definitive inscriptions confirming such uses have been found within the shafts themselves.

Systematic excavation and documentation of the Sphinx began in the 19th century under figures such as Giovanni Battista Caviglia and later Émile Baraize in the 1920s–1930s. In modern times, the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, along with scholars like Dr. Zahi Hawᴀss, has overseen extensive conservation and research projects. International collaborations involving geologists, archaeologists, and engineers continue to study erosion patterns and subsurface anomalies. Despite centuries of study, the Sphinx remains an evolving archaeological subject, embodying both the achievements and unanswered questions of ancient Egyptian civilization.