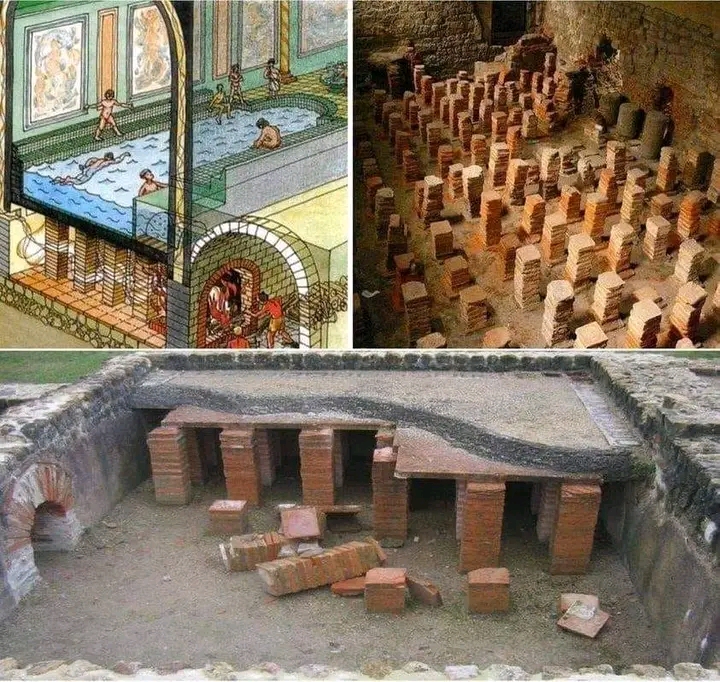

Beneath the vanished marble floors of the Ostia Antica baths, a skeleton of brickwork remains. This is not a ruin, but a fossilized nervous system—the hypocaust, the radiant heart of Roman bathing culture, engineered between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. In a world without electricity or modern fuels, the Romans mastered comfort through an elegant, invisible physics of fire, earth, and air.

The system is a masterpiece of practical thermodynamics. Rows upon rows of short, sturdy brick pillars (pilae) rise from a concrete base, forming a silent, subterranean forest. Above them, the grand floors of the caldarium (H๏τ room) and tepidarium (warm room) were suspended. In a separate furnace room, a slave—the fornacator—would stoke a perpetual fire. The H๏τ gases, instead of escaping uselessly, were channeled beneath this raised floor. They snaked through the grid of pillars, heating the thick concrete and tile above until it glowed with a steady, even warmth. The same gases then escaped through box flues embedded in the walls, ensuring the very structure breathed heat.

To stand in this hollow, sooty space is to witness the marriage of brute force and exquisite intelligence. This was not just heating; it was environmental design. It enabled the luxurious social ritual of the baths, a cornerstone of Roman life, by engineering a reliable, diffuse warmth that banished damp and chill. It speaks of an empire that applied the same systematic logic to personal comfort as it did to aqueducts and roads.

Now, the space is a silent geometry of dust and cool brick. The roar of the furnace is gone, the steam and chatter of the bathers long dissipated. But the hypocaust remains, a patient and precise armature. It tells a story not of lost luxury, but of enduring ingenuity. In the clever, enduring design of these humble brick pillars, one feels the quiet truth that the most profound innovations are often those that work unseen, serving human desire so well that they outlast the very pleasures they were built to provide.