The structure depicted in the image is a monumental stepwell, widely identified as Chand Baori, located in the village of Abhaneri, Rajasthan, northwestern India. Archaeological and historical evidence dates its construction to approximately the 8th–9th centuries CE, during the reign of King Chanda of the Nikumbha dynasty. Stepwells emerged in arid and semi-arid regions of the Indian subcontinent as sophisticated responses to seasonal water scarcity. Although Chand Baori was never “lost” in the modern sense, systematic archaeological documentation and conservation began under the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, recognizing the site as a masterpiece of pre-modern hydraulic architecture.

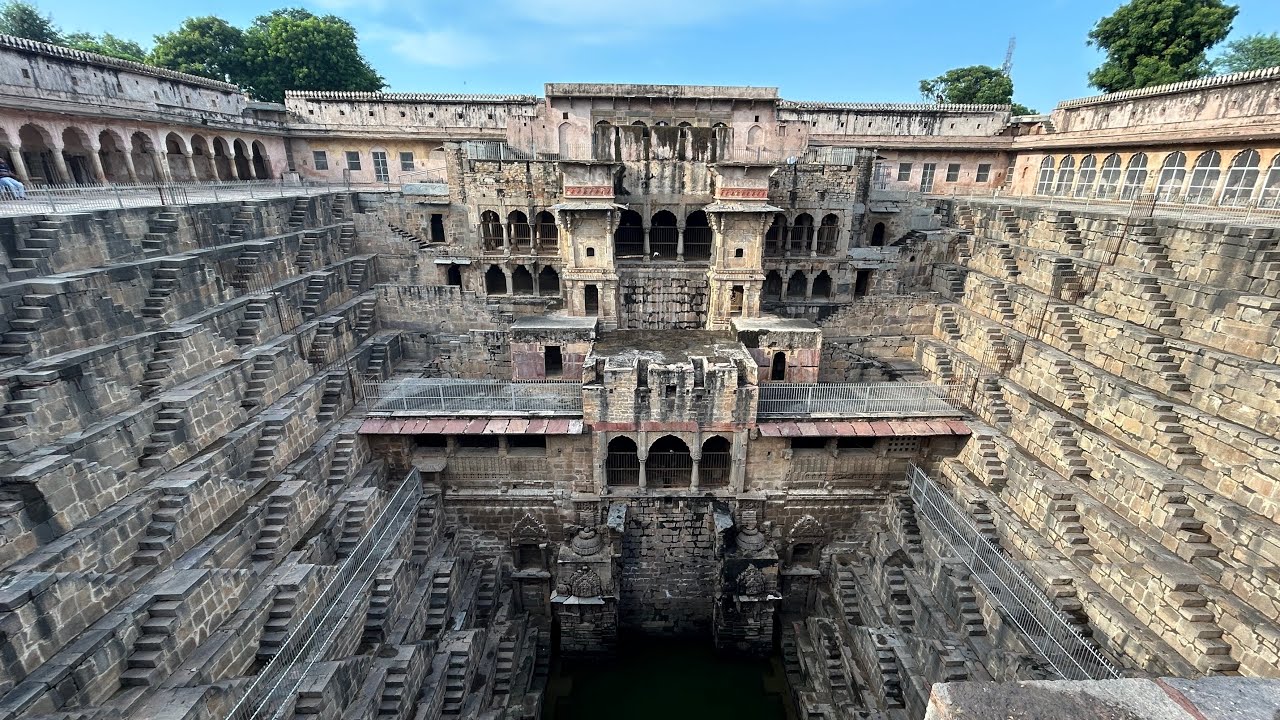

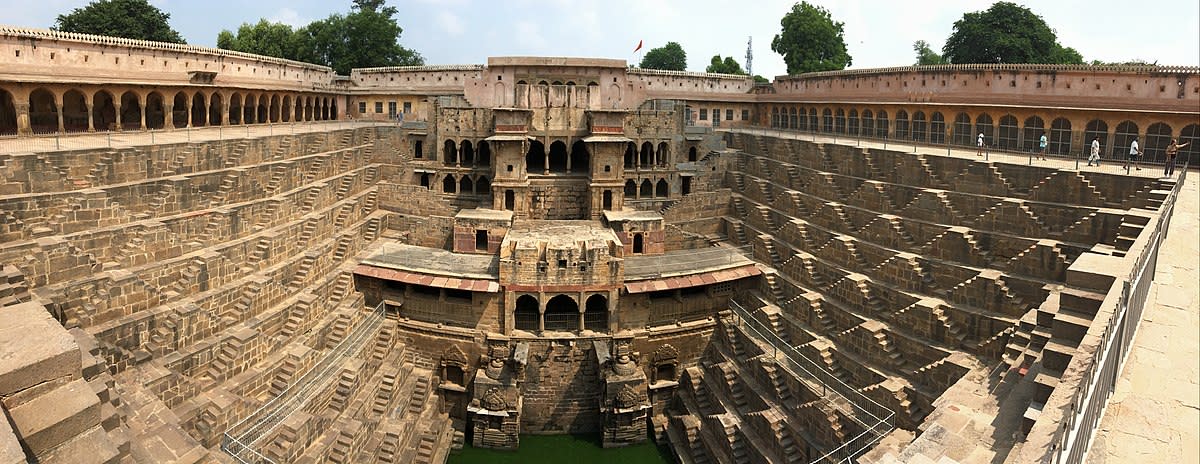

Chand Baori was constructed primarily from locally quarried sandstone and limestone, materials well suited to both structural durability and precise carving. The well descends approximately 20 meters and consists of more than 3,500 narrow steps arranged in a concentric, geometric pattern across multiple tiers. Each stone block was individually cut, dressed, and set without mortar, relying on gravity, precision, and friction for long-term stability. The spiral-like recession of the steps is not merely decorative; it maximizes access to water at varying levels throughout the year while distributing structural stress evenly along the walls.

The complex geometry of Chand Baori reflects advanced mathematical planning and a deep understanding of structural mechanics. The repeтιтive zigzag pattern of steps creates visual rhythm while serving practical functions: minimizing erosion, reducing slippage, and enabling crowd movement. Peripheral galleries, landings, and shrines were integrated into the design, transforming the well into a multifunctional architectural space. From an archaeological perspective, the structure demonstrates how engineering, geometry, and environmental adaptation were inseparable in early Indian construction traditions.

While Chand Baori primarily functioned as a water reservoir, it also served important social and ritual roles. Stepwells were communal spaces where people gathered for water collection, rest, and religious observance. The cool microclimate created by the descending stone levels made the well a refuge during extreme heat. Proximity to the nearby Harshat Mata Temple suggests ritual ᴀssociations, where water drawn from the well was used in purification and worship. Archaeologically, Chand Baori illustrates how water management was deeply embedded in spiritual practice and community life.

Chand Baori has been studied and conserved primarily by the Archaeological Survey of India since the colonial period, with further research conducted by architectural historians, hydrologists, and archaeologists. Modern methods such as pH๏τogrammetry and structural analysis have confirmed the long-term stability and efficiency of the design. Archaeologically, Chand Baori is significant not only as one of the deepest and most elaborate stepwells in India, but as evidence of a sophisticated, non-industrial engineering tradition capable of monumental construction. It challenges modern ᴀssumptions about pre-modern technology and stands as a lasting testament to human ingenuity in managing scarce resources.