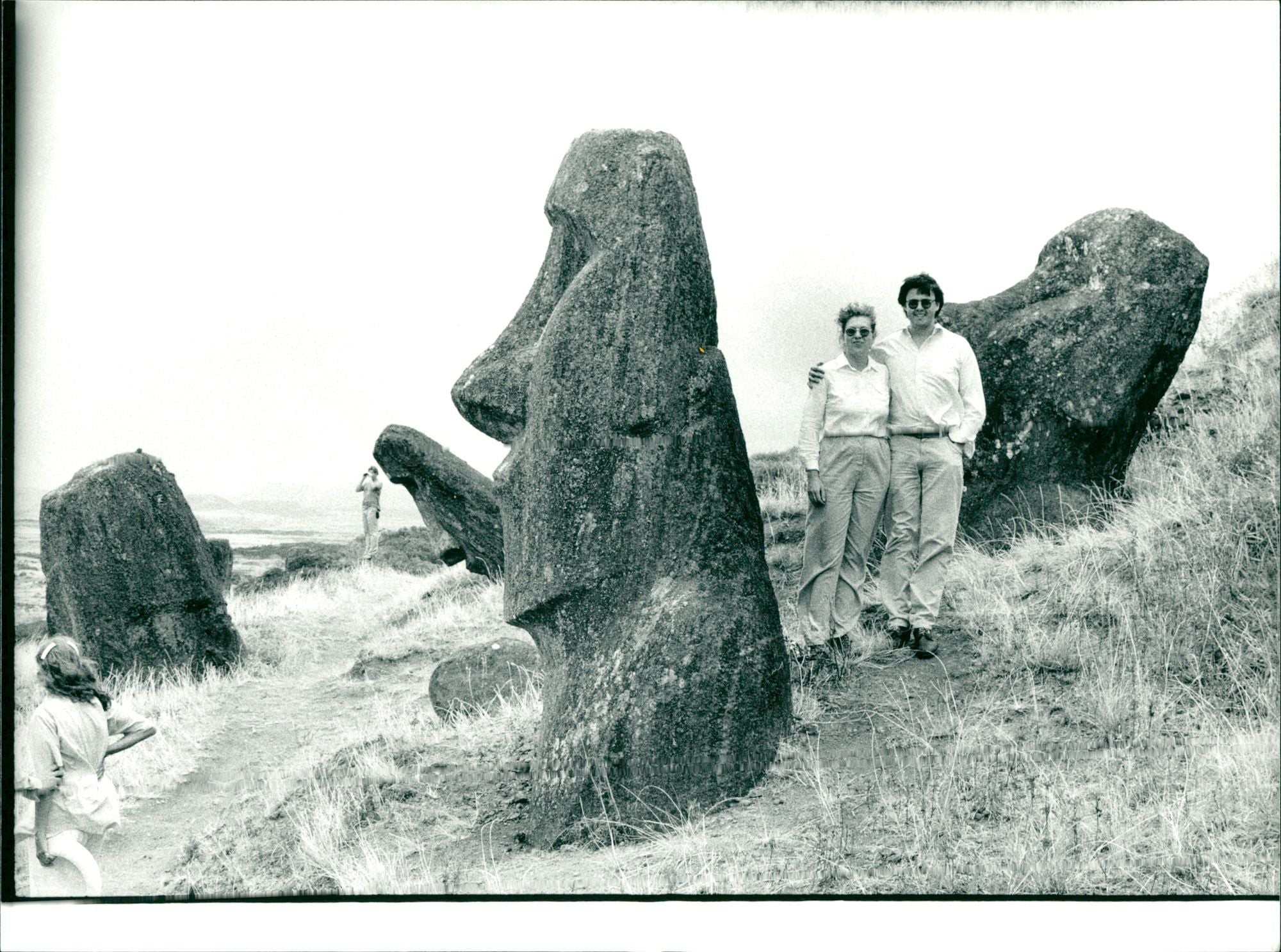

This is not the iconic, isolated silhouette against a sunset sky. This is a different truth: the Moai in the midst of life. Taken in the early 20th century, the image captures a profound, fleeting moment of temporal overlap. The giants are not yet fully relics; they are still neighbors.

They rise from the volcanic soil of Rapa Nui not as pristine icons, but as beings caught in a slow-motion stumble. Some stand proud, their elongated torsos and heavy brows casting long shadows. Others are partially buried, the earth embracing them up to their chests, as if they are being gently reclaimed. Their faces, carved with supreme confidence centuries before, are now softened by salt wind and rain. Many noses, once the proud, defining ridge of their profiles, are broken—not by violence, but by the patient, accumulated weight of time and gravity. They are unfinished thoughts, their meaning beginning to blur at the edges.

What transforms the scene is the life that swirls around them. Horses, introduced by a new world, graze casually at their feet. People, perhaps islanders or early researchers, move among them, their scale rendering the giants both immense and strangely approachable. There is dust in the air, the smell of grᴀss and animal, the mundane sounds of a day. This is the crucial, heartbreaking layer: for a brief historical moment, the Moai are not yet cordoned off by archaeology, not yet fully translated into the language of “mystery.” They are presences in a working landscape. They share the same light, the same ground, the same air as the living.

To look at this scene is to feel time collapse in a uniquely intimate way. The 13th-century act of creation—the quarrying of the soft volcanic tuff at Rano Raraku, the epic choreography of moving these multi-ton figures across the island with ropes and log rollers—feels impossibly distant. Yet, the early 20th-century moment of the pH๏τograph feels immediate, almost familiar. The Moai bridge that gap. They are no longer distant myths; they are witnesses who have seen the world change around them. They watched the forests fall, the society that carved them transform, and new peoples and animals arrive.

They stand as a powerful reminder: monuments are not born ancient. They are born contemporary, urgent, and full of specific meaning for the people who made them. They become ancient only later, after the language that explained them fades, the rituals that animated them cease, and the world that understood them as partners turns them into puzzles. In this pH๏τograph, that process is beautifully, tragically incomplete. The Moai are caught between being working deities of a place and becoming global symbols of isolation. They remind us that every relic was once a neighbor, and every silent giant once lived in a world of sound, movement, and shared breath.